Even if the 19th edition of the Venice Architecture Biennale is not resolutely African, like the one Lesley Lokko imagined for 2023, it is nevertheless characterized by a significant presence of voices previously seen as marginal. Within this very dense and pragmatic exhibition, which has a global resonance, the ideas that come from the continent and the diasporas not only have their place, but they also have the strength to be heard. Even though they do not always benefit from the support and recognition of African institutions and from the people of the continent. Let’s have a look at what is actually going on in Venice!

Author: Luisa Nannipieri

Two years ago, for the first time in its history, Africa was the protagonist of the Venice Architecture Biennale. Lesley Lokko, the event’s first curator coming from the continent, carried out a remarkable groundwork which has left a lasting mark that is still making waves. The paradigm shift is noticeable even in this new 19th edition of the Biennale (ongoing till November 23), curated by the Italian architect and urban planner Carlo Ratti. Ratti, who lives and works in the United States, has always kept an eye on the scene developing in Asia and in the rest of the world, the Global South included. His exhibition is dubbed “Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective” and it translates as a statement about how we urgently need to address the social and environmental challenges that are currently shaking the world. It invites us to make a leap in sustainable architecture and promotes cooperation and transnational work. In the hope that collective intelligence will show us ways to adapt to the future that awaits us.

To this end, Ratti reminds us that it is essential to listen and be inspired by the diverse voices that come from outside the well-established narrative of the Western architectural world: “For the first time in the history of the Biennale, we have launched a call for applications for the exhibition taking place at the Arsenale (the former shipyard in Venice and the symbolic location of the event). An open call that was a very difficult act, but also magnificent. Difficult because we were inundated with applications. But at the same time beautiful, because we found voices that we would not have been able to find otherwise. Those voices came from the other side of the world, or were yet to be heard, like those of the students who had just left university”. This gave birth to a very dense exhibition, imagined as a large fractal organism where the works of more than 750 participants resonate with each other. This incredible number of participants is definitely a first, in Venice. And, of course, several of them live in, work with, or have ties with the African continent. For those who have had the occasion to see Lokko’s Biennale, several practitioners named in this article will certainly stand out, as they previously made an appearance in the Guests from the Future’s sections, she personally curated.

The work of the Nigerian architect Tosin Oshinowo, An Alternative Urbanism: Self-organising Markets of Lagos, has been especially appreciated by the international jury, which awarded the project a special mention award for its insight into the everyday innovation that drives many African cities. Through three documentary films, the project reveals the systems, practices, and ingenuity embedded in the Ladipo, Computer Village, and Katangua markets. Where you can find second-hand car parts, electronics, and recycled fashion. These spaces actually function as informal factories, processing end-of-life products from the Global North and embodying the principles of circularity. Oshinowo, who is based in Lagos, has been fascinated by this collective process and has chosen to show it using an optimistic narrative, rejecting the common voyeuristic representations of African spaces. The research project tries to understand how the urbanization of the continent has created an urban condition that is alternative to conventional expectations of progress and development.

Several other African and diasporic projects, both theoretical and pragmatic, can be spotted across the huge L-shaped venue of the Arsenale. They are scattered in the three main thematic worlds, or sections, composing the exhibit: Natural Intelligence, Artificial Intelligence and Collective Intelligence. But we can also find some of them in the extra section called Out, where the visitors are asked if we can really look at the space to find a solution to the crises we face on Earth. The non-exhaustive list features a modular kitchen project by Design for Communities, which delivers 300 meals a day to children in the Mathare slum in Nairobi. An educational and co-designed project in Uganda focusing on urban planning and sustainable practices (The Kitintale Collective). Or a study on bungalow compounds in Johannesburg, which in the post-colonial era were transformed into informal and flexible living spaces.

Courtesy of the Pavilion of the Kingdom of Morocco

It is also worth mentioning the philosophical work of South Africa’s practitioners Mphethi Morojele and Kgaugelo Lekalakala, proposing an architecture inspired by the culture and needs of animist societies. The suggestions around building an adaptive health architecture in rural Kenya, based on artificial intelligence, made by Geoffrey Mosoti Nyakiongora with Bridging the Health Divide. A philanthropic project coordinated by a Catalan university in Tanzania, which includes a multipurpose building made from 3D-printed earth. Or the Probiotic tower by the Egyptian firm Design&More, envisioning the transformations of Cairo’s abandoned water towers into independent vertical ecosystems.

In the Out section we can find a piece by Olalekan Jeyifous entitled Even in Arcadia… which draws inspiration from the Arcadian myth to juxtapose picturesque portrayals of idyllic pastoral life with glimpses of a retrofuturist urban protopia set within the Hudson Valley, New York. And catch a glimpse of the journey of Senegalese astronomer Maram Kaire. A man who, at the head of a NASA mission, blends modern science and Senegalese astronomical tradition to shape the conversation about a sustainable future in his own country.

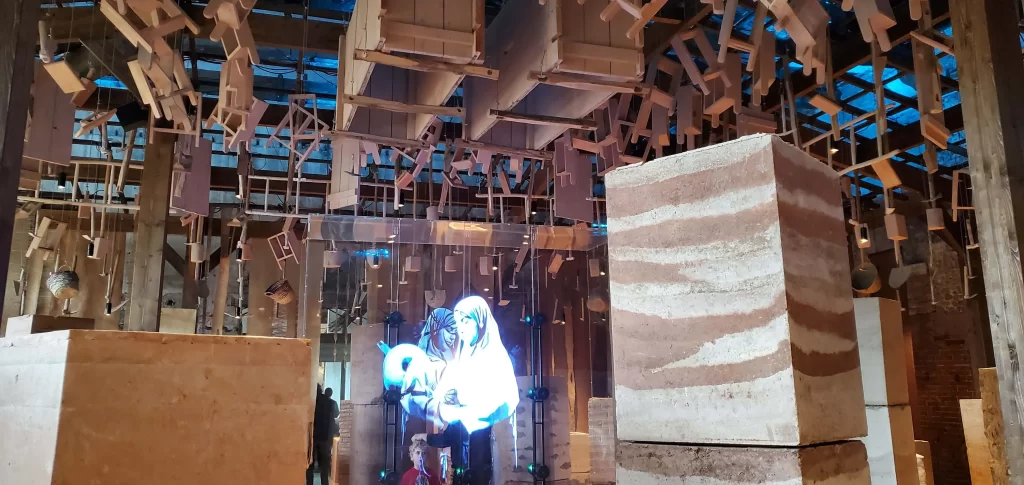

Besides the exhibition designed by Carlo Ratti, the Arsenale also hosts some of the national pavilions, such as the Italian, Chinese or Saudi. Morocco has also occupied a large room of the venue with an installation called Materiae Palimpsest, which offers an immersive experience in the world of earthen construction in the Kingdom. Visually striking, complete with holograms of artisans, a labyrinth of stone and earth columns, and even a ceiling covered with work tools such as shoves and wooden handcarts, the exhibition is curated by two architects still mostly unknown in the country (Khalil Morad El Ghilali and El Mehdi Belyasmine), and it has generously been funded by the State. The proclaimed goal was to highlight the country’s expertise on vernacular architecture, but on site we could hear several Moroccan practitioners harshly criticize the results: “There is very little substance, it’s nothing more than folklore and a flashy show”, “It’s a lost opportunity”, told us the most skeptical.

Indeed, one might wonder why not showcase the work of local architects who are experts in the field of neo-traditional and sustainable architecture, such as Aziza Chaouni or Salima Naji. Chaouni, who is an associate professor at the University of Toronto and specializes in the implementation of sustainable technologies and adaptive reuse in developing contexts, recently received international recognition for her innovative, low-cost prototype of a rammed-heart house in Morocco’s Haouz region, which was devastated by an earthquake in 2023. Salima Naji, an architect and anthropologist, has been working for more than 20 years around the preservation of Saharan collective architectures, and she is known for her contemporary projects with a social character. She is one of the laureates of the 18th edition of the Global Award for Sustainable Architecture, supported by Saint-Gobain and UNESCO, which was announced in Venice at the same time as the Biennale opening.

Both of them are actually present in Venice, participating in talks and showcasing some of their works at the invitation of the Qatari pavilion.

Beyti Beytak © Giuseppe Miotto - Marco Cappelletti Studio

Beyti Beytak © Giuseppe Miotto - Marco Cappelletti Studio

The Gulf State is set to soon build its own venue in the Giardini, the garden where the prominent nations such as the UK, France, Brazil, or Japan historically have their statement pavilions. But, for its first participation in the Biennale, it is showcasing works centred on the common features of the architecture of the MENASA region in the magnificent setting of the former Franchetti Palace. The exhibition, titled Beyti Beytak. My home is your home. La mia casa è la tua casa, explores hospitality and shared spaces, honouring architects such as Egyptian Hassan Fathy, one of the first to advocate a return to sustainable vernacular architecture, and his compatriot Abdel-Wahed El-Wakil, one of the masters of contemporary Islamic architecture. It also features the work of the young Algerian architect and activist Meriem Chabani, with the project for a cultural centre in Myanmar she designed with her studio New South, and the work of French architect and historian André Ravéreau on the oases of the Sahara.

Togo is another notable first-time participant at this Biennale and the only sub-Saharan African country represented this year. In this case, the government has not been actively involved in the project. If the Republic of Togo came to Venice, it is thanks to the impressive determination of the founding director of the Palais de Lomé, Sonia Lawson, who has been reflecting on the historical and cultural importance of architecture in her country since the renovation of the Palais, the largest visual arts centre of the country. “I am delighted to commission the first Togolese Pavilion at the International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia”, said Lawson. “It is a milestone to showcase Togo’s diverse architectural heritage to a large number of visitors from across the world. The Palais de Lomé is a landmark architectural venue in Togo. Once a place of colonial exclusion, the institution’s program engages in a dialogue about contemporary issues relating to culture, architecture, and the environment. I hope the pavilion furthers the conversations on the future and preservation of architectural heritage in West Africa”.

The project, entitled Considering Togo’s Architectural Heritage, has been curated by the architecture and research firm Studio NEiDA (Jeanne Autran-Edorh and Fabiola Büchele) with the participation of Sabrine Bako. It takes the form of a photographic exhibition, a real gem, exploring the country’s architectural narratives from the turn of the 20th century, focusing on the themes of conservation and transformation. The methodical documentation of Togo’s iconic architecture lead by Studio NEiDA, establishes a dialogue between conventional building practices and modernist construction techniques and it has allowed to restore the names of the local architects who worked on the projects and had been erased from the official history.

Beyti Beytak © Giuseppe Miotto - Marco Cappelletti Studio

The show especially highlights Afro-Brazilian architecture, a style developed by freed slaves returning from Brazil, and the remarkable examples of modernist structures built after the independence. Some of the outlined buildings are still functional, such as the ECOWAS and the BOAD banks headquarters. It is quite interesting to note that the West African Development Bank (BOAD) has been actively preserving the building, the design of which is inspired by the traditional Batammariba architecture of northern Togo, specifically the tata somba (earth houses) of the Koutammakou region.

Other structures showcased in the exhibit have benefited from renovation. Particularly noteworthy are the refurbished Hotel 2 Février and the Palais des Congrès, which is in the process of restoration. But other prominent buildings, such as the Hotel de la Paix and the Bourse du Travail, are in a state of disrepair, completely dilapidated and threatened with destruction. Studio NEiDA has actually designed a renovation project balancing social impact and preservation for some of those sites, but their proposal met with the indifference of the Togolese institutions. “If bringing this project to Venice allows us to highlight our architectural heritage and history”, believes Jeanne Autran-Edorh, “perhaps they will also change their approach and their stand on the matter.”

The efforts of the Togolese team have been well received and recognized internationally, putting the country’s architecture under the spotlight. This success, despite the lack of interest of the institutions in participating in the Biennale, raises some questions about the means by which African countries can establish themselves on the international stage. The partnership involving private or non-governmental arts institutions – or platforms – and the talented voices of the continent and its diasporas, is definitely a valid option, as the Togo’s example shows. It’s undeniable that events like the Venice Biennale still have an appeal. Especially when we consider that even now many people on the Continent base their scale of values on the Western one. Seeing the ideas coming from the South recognized in the global North, such as the importance of using vernacular techniques to build better in a global warming context, gives them more strength in their countries of origin. It can be frustrating, but it is still a reality African practitioners need to deal with.

La Biennale Di Venezia

La Biennale Di Venezia

Leaving behind the Togo pavilion, nested in a quiet and charming building outside the touristic routes, just across a small bridge behind the Arsenale, we take the vaporetto towards the Giardini. The last stop of this Venetian tour still has a lot to offer. Starting with the magnificent temporary pavilion, made of recycled wood and glass, that Rolex commissioned from the Nigerian architect Mariam Issoufou (already Kamara). The pavilion features a wooden facade, crafted locally from recycled wood beams, and fashioned to evoke the fluted bezel of many of Rolex’s iconic watches. Inside, the translucent coloured ceiling – made by Murano glassmakers – produces a range of shades and hues that morph throughout the day. The terrazzo flooring is made of an aggregate that includes recycled “Cottisso” crushed glass. The ecological vulnerability of Venice, as well as Rolex’s commitment to craft, was her inspiration for the project. Issoufou has an intersectional approach to sustainability, one that extends beyond environmental factors, and she made sure that the pavilion promotes the social fabric, cultural history, and economic conditions of crafters in Italy, and more specifically in Venice itself.

Let’s Grasp the Mirage is the name of the interactive exhibition showcased in the Egyptian pavilion (Egypt is the only African country disposing of a permanent venue in the Giardini). Curated by Salah Zikri, Ebrahim Zakaria, and Emad Fikry, and commissioned by the Ministry of Culture Egypt and Accademia d’Egitto, the project reflects on the delicate balance between conservation and development, centring on the oasis seen as a microcosm and a symbol of sustainability. The core of the installation is a 10 meters long platform suspended above a sand-covered floor, where visitors can place and shift yellow and blue-gray blocks, representing conservation and development. Each of them comes in a different size and weight: their disposition can create a visual and physical equilibrium, taking part at the same time in a game of balance that visualizes the complexity of sustainability and the impact of uneven decisions.

Speaking of national contributions, it is interesting to talk about how the French and British pavilions approached this year’s Biennale. Keeping in mind that Great Britain has been awarded a special mention for National Participation by the Biennale international jury for its ability to “reveal architecture as architecture that is defined by extraction that produces inequality and environmental degradation and it attempts to imagine a new relation between architecture and geology”.

Domino 3.0: Generated Living Structure

Zucca Projects Venice venue

The British pavilion exhibitions have been commissioned by the British Council since 1937 and this year intervention is the result of an open call, launched in November 2023, for innovative proposals for a collaborative exhibition. It is actually a key part of the British Council’s UK-Kenya Season 2025: a year of cultural exchange and a partnership which celebrates the connections between the two countries. Entitled GBR – Geology of Britannic Repair, the exhibition is curated by a collaborative team based between the UK and Kenya, including Kabage Karanja and Stella Mutegi of Nairobi-based architecture studio Cave_bureau, and it investigates how architecture can reverse the destructive impacts of colonial systems of geological extraction.

The exhibition’s geographical, geological and conceptual focus stems from the British Pavilion’s pivotal alignment along an axis that runs between Britain to the north-west, and the Great Rift Valley to the south-east. Emerging from the “rift”, which runs from southern Turkey through Palestine, the Red Sea to Ethiopia, Kenya and Mozambique, the exhibition comprises a series of installations by Cave_bureau, Mae-ling Lokko and Gustavo Crembil, Thandi Loewenson, and the Palestine Regeneration Team / PART.

The central gallery of the pavilion becomes, for instance, an Earth Compass: the space is crowned by an image of the night sky above Nairobi on 12 December 1963, the day of Kenya’s independence from British control, paired at the centre with a pulsating “oil drum” that unsettles the corresponding depiction of the sky above London on the same date. On the surrounding walls is a cartography of the carbon emissions brought about by geologic empires, with the keloid “scars” creating an inverted index of cumulative national carbon emissions from 1750–2023. Visitors can then experience The Baboon Parliament emerging both from a reproduction of the rift valley’s caves and the brick structure of the pavilion itself, before approaching Objects of Repair. An installation exploring fracture and repair in the architectures and geologies of Palestine.

Song of the Cricket

Italy and the Intelligence of the Sea,”

curated by Guendalina Salimei

A moving series of graphite drawings by Thandi Loewenson is hung on the walls of a crimson piece amongst bits of poetries. It is inspired by the technofossils orbiting around our planet, which testifies the history of imperialist expansion above the heart. He chooses to re-write the scenes of exploitation and extraction the extra-terrestrial ambition facilitated on the ground depicting Njiwa, the sixth rocket developed by the experimental aerospace company Développement Tous Azimuts based in Democratic Republic of Congo; Cyclops 1, the inaugural prototype of the 1964 Zambian Space Programme, launched by “space girl” and liberation combatant Matha Mwamba; and a mission data-gathering cube developed by the Mars Society of Kenya. In his works, recyclers, ‘artisanal miners’ and waste-workers recuperate discarded sites and resources, forging new collectives between people and the planet and become the architects of our possible future.

The British exhibition ends with Vena Cava, a timber frame reproducing the Palm House at Kew Gardens in West London, the beating heart of the British botanical empire and the world’s first large-scale greenhouse, the focus and destination for a vast system of extraction and circulation of plants, minerals, energy, labour, and knowledge. From the frame are hung patterned panels of fly ash, biomass, bioplastics, and fungi – emerging twenty-first century material streams that herald a shift away from thin mineral-based building envelopes dependent on mechanical environmental regulation, which the Palm House pioneered.

Just below the British pavilion, the French pavilion’s renovation site has been transformed into adaptive architecture and an exhibition space. Among the approximately 50 showcased projects exploring the theme of Vivre avec / Living with, selected by architects Jakob and MacFarlane in association with Martin Duplantier and Éric Daniel-Lacombe, several have a connection to Africa or were designed by its architects. Such as MycoHab, a pilot project in Namibia born from a collaboration between the MIT, Standard Bank Group and Cleveland-based Redhouse studio and a peculiar example of regenerative architecture. MycoHab is actually a house made entirely of bricks produced locally, using only agricultural waste products and the natural process of mycelium growth. Namibian bush is used as the substrate to grow gourmet mushrooms, and the waste of the cultivation can be used to make carbon-storing structural materials. We can also mention the Pedagogic complex of Timenkar, in Morocco, by the aforementioned Salima Naji. Or the reconstruction of the big Central Market of Kinshasa, imagined by the French studio Think Tank following the principles of tropical brutalism.

The African School of Architecture and Urban Planning Professions (Togo) and the Ain Shams University (Egypt) both presented their studies and propositions, respectively, on the issue of marine submersion in the Ivorian city of Grand-Bassam and the noise pollution in Cairo. While the French University of Egypt showcased Siwian House: a contemporary vision responding to the aspects of extreme heat and the threat of salinization.

Yet another demonstration, if needed, that African architecture has potential. Even if it is often easier to showcase it abroad or capitalize on it when working on projects involving transnational teams, than to get the recognition it deserves in one’s own country.

It is another paradigm, that of mentalities, that it’s definitely time to change.